Author of the interview: Barbora Pešek • Photo: Mohamed Saidu Bah

Silvestr Tkáč

Silvestr Tkáč worked as a logistics officer for Doctors Without Borders. Subsequently, he started an interesting initiative within the organization in cooperation with the Czech company Prusa Research, one of the largest manufacturers of 3D printers in the world. The aim of the project is to change the way missions receive key materials and components through 3D printing. Prior to joining Doctors Without Borders, he was involved in 3D printing in The Gambia, where he founded Make3D, a product development, manufacturing, consulting and training company in 3D printing for hospitals, schools and in support of local entrepreneurs.

What is the role of 3D printing alongside other technologies you use in humanitarian missions?

Our primary focus is medical relief. 3D printing is and always will be a fringe technology. Our 3D printing for all project started a year ago in June and I have been finding over the last year that there are still a lot of initiatives in the organization that are using this technology. One of our goals is to unite the organisation in terms of sharing know-how. We want 3D printing to be seen as one of the common tools, like radios or other communication technologies.

The covid pandemic showed the possibilities of 3D printing - shields or fans were printed. It also showed the strength of the community around 3D printing and that there was no need for a logistics chain to transport it to the necessary location. So do you still need to "convince" anyone of the role of 3D printing?

Although awareness spread a lot during the covid, it is still relatively small. Most colleagues have heard that 3D printing exists, but they imagine it in two extreme cases - either that advanced titanium bone replacements can be printed, or, conversely, small children's toys. To be able to use a 3D printer on a mission, we need to move from both extremes to somewhere in the middle.

What do you print most often?

We print things that are useful for everyday use. Either we're replacing a non-existent item - like when something breaks, improving items (adding handles, personalizing), or solving specific problems for which there isn't a solution anywhere else yet. It's a low-maintenance print for post-processing and maintenance. Our main focus is printing from affordable printers and materials.

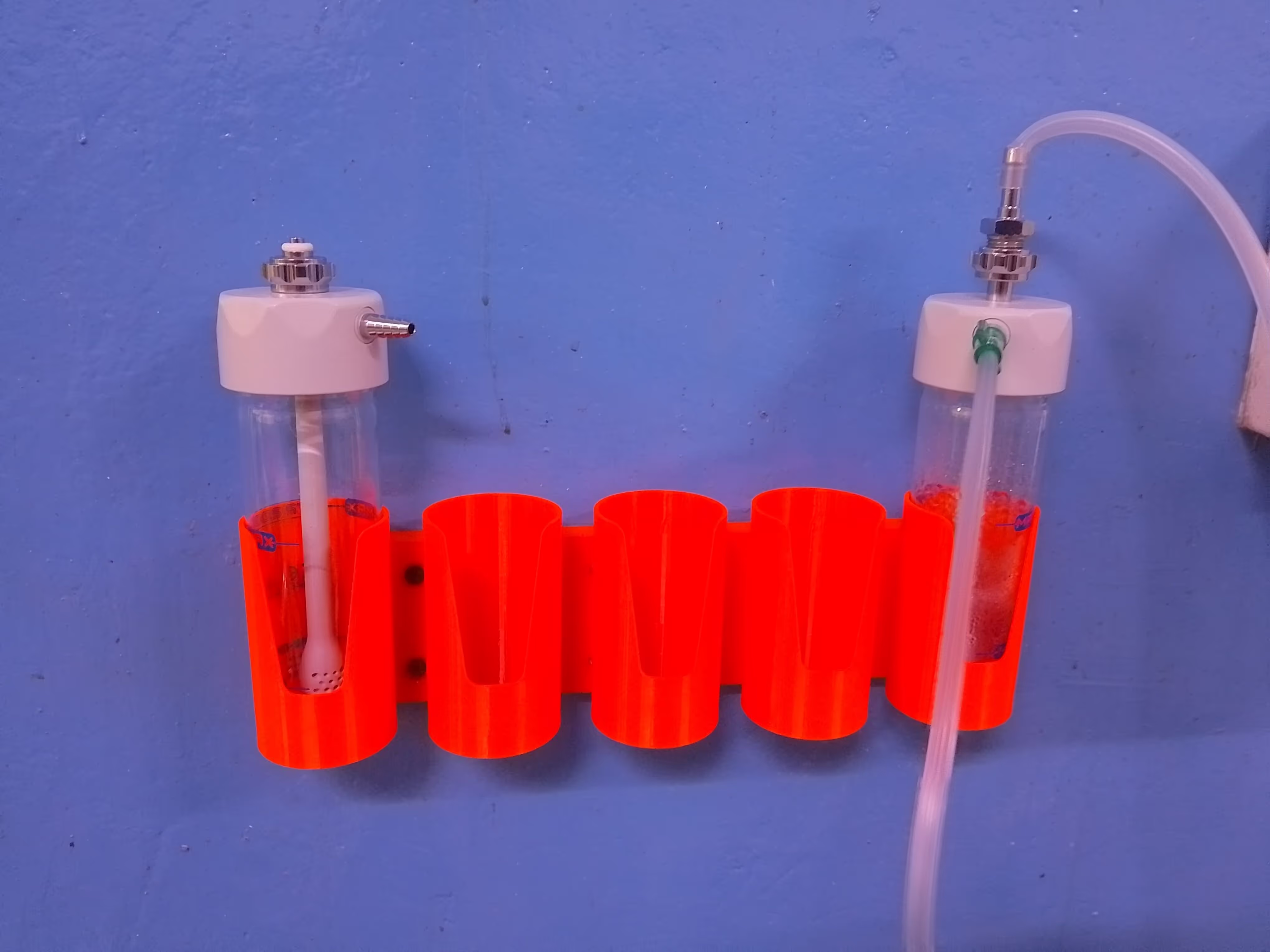

A humidification tube placed in a holder printed on a 3D printer at the children's ward of Magburaka Government Hospital, Tonkolili District, Sierra Leone. Photo: Silvestr Tkáč

Do you have a database of models? One that can include other open hardware projects and things that someone else has modeled?

It's one of the directions we're going in. We have a public repository where we upload models. It's available on Printables on the official profile called Médicins sans frontiérs.

What do you think are the main steps to expand open hardware projects to be able to include them in your missions?

I think these projects are often very DIY. They contain various components that are needed, but they have to be ordered and they are waiting for them.

For us, it's essential that they are already invented as a kit - like OpenFlexture (OpenFlexure Microscope is an open-source 3D printed microscope designed for low-cost and portable scientific and medical use, ed.).

For me, it makes a big difference whether I spend six hours or several days assembling it. Often, parts for open hardware projects are then ordered from China, for example. So from my point of view, it's essential that these projects are not so DIY, but that they come in some kind of complete package that is easy to find and all the parts arrive at once.

Lab manager Ibrahim Massaquoi stands in front of a 3D printer holding a 3D printed model of an adult male tibia specimen at the MSF office in Makeni, Bombali District, Sierra Leone. Photo: Mohamed Saidu Bah

Engaging the international 3D printing community

There are an estimated 30-50 million people in the world who can 3D model. What plans do you have for engaging this huge community in humanitarian projects, not only at Doctors Without Borders, but in other open hardware projects?

Of course we are thinking about the 3D printing community. In our experience, people like to use their knowledge for a good cause and for something useful. We see this not only in the 3D Printing for All project, but also in the Missing maps program, for example, where the corporate community is also involved in mapping in different locations. These maps are then used by our colleagues directly on the mission.

What are the challenges now in working with the modelling and 3D printing community?

The main challenge is that there is not much time to draw different sketches, measure in all dimensions and details. Colleagues on the mission often don't know how to draw technically because they have expertise in other areas. Another challenge is directly related to how to reach the community.

On the Doctors Without Borders podcast, you said that in South Sudan, for example, you can't get filament. How are you addressing that?

We bring what we call a 3D printing kit. It's a package containing a printer, filament, tools and spare parts - everything that should last a project for about a year, based on how much we're going to print.

What does your "3D printing kit" look like that you send on missions?

We supply four main types of filament, which we match all the things we print to. It's not immutable, but the goal is to standardize the kit so we can send it anywhere in the world and be able to make a reasonable set of our stuff.

How do you try to get local collaborators excited about 3D printing and how does the training process work?

For a lot of people, all they have to do is see the printer and they get excited - including me. We also try to spread awareness of 3D printing so that when the printer is on a mission, it doesn't have to be used strictly for things in hospitals or offices. Colleagues can print something for themselves, which they do. Formal training usually has two parts - one part online and one part offline. Our goal is to have everything online so that it doesn't limit us in what places we can physically get to.

How does the training of colleagues work and what is the long-term benefit of 3D printing after you leave the mission?

Most of our projects are up to 90 percent based on local colleagues, which is our main target group for training. We are all about keeping the know-how on the ground. It's up to them how they use it and where they take that expertise next.

One of our IT specialists from Sierra Leone, for example, is so enthusiastic about 3D printing that he wants to get a printer for his home, is learning 3D design and would like to get involved in our project internationally - for example, to travel to other countries and train other colleagues.

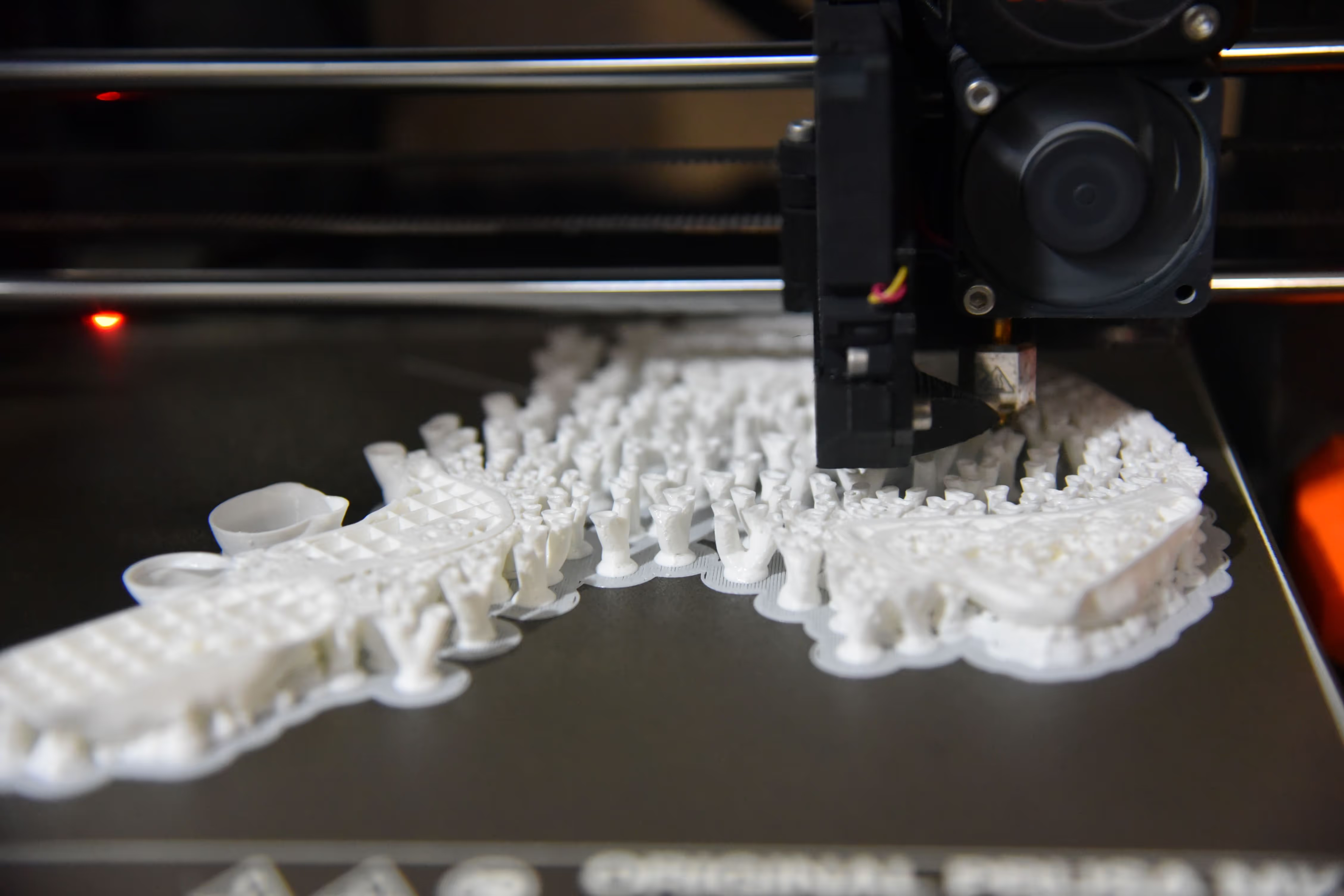

Detail of a 3D printer on a mission in Sierra Leone. It prints a plastic pan that will be used to train midwives at Magburaka Hospital and Hinistas Community Health Centre in the Tonkolili District of Sierra Leone. Photo: Daniel Garcia/MSF

There are better technologies for making weapons than 3D printing

What are the future challenges for 3D printing and society in a world where anyone with a printer can print a working weapon?

This is, of course, a theme that is emerging in our country as well. There is a concern that the printer could be used for something it is not intended to be used for. We prevent that, of course, by administrative procedures. We control what each printer prints, who wanted access and how, and so on. I always say with exaggeration that there are better technologies for making weapons than 3D printing. This is a very popular topic in connection with cases in the United States, and it is mainly about printed firearms. I don't think this issue would be that big. 3D printing is just a tool and it's up to people how they use it. However, there must be some administrative procedures and prevention. For example, we don't leave the printer unlocked so that no outsider can access it at any time.

What is the biggest topic for 3D printing right now?

I see the biggest challenge in terms of the legislative framework and regulation. The discussion that's going on focuses on what's legally possible and morally right in terms of spare parts, for example. The legislative framework is crucial.

When I applied for certification of a 3D printed medical device in The Gambia a few years ago, the authority there had no idea what 3D printing was. We eventually got the certification, but we had to provide a bunch of documentation, including how the printing works and so on. And that's just one gadget and one small country.

I think it's similar to the internet. In the beginning it was very much kind of organic and then it became apparent that we needed to give it some kind of framework. It doesn't have to be about restricting, but more about letting the user know what's possible and what's not.

Two pipettes on a 3D printed holder in the Magburaka Government Hospital laboratory. Photo: Silvestr Tkáč

3D printing is regulated differently in each country. How do regulations affect your work on missions?

So far, we're mainly printing so-called non-critical parts. If any 3D printed part breaks, it won't endanger anyone. We don't print things that bring anything into patients' bodies or anything that's in direct contact with the patient. So far.

But as awareness of our project and 3D printing in general spreads, discussions are arising that are bringing a lot of opinions, and I'm very happy for them. I can imagine that we will go further in the future by introducing stricter procedures, for example, in the approval process. In addition, with the advent of various more advanced materials, we will also be able to print stronger components that can withstand higher temperatures.

What is the situation in the Czech Republic?

I don't like to put myself in the role of someone who can judge the situation in the Czech Republic. There are groups in various fields, including medicine, that are working on legislation. In the Czech Republic it is the Czech Society for 3D printing in medicine. The know-how exists and stands (and often falls) mainly on the excellent work of experts in specific medical institutions or universities. But of course, the applications in the Czech Republic are different from those of Doctors Without Borders on missions.

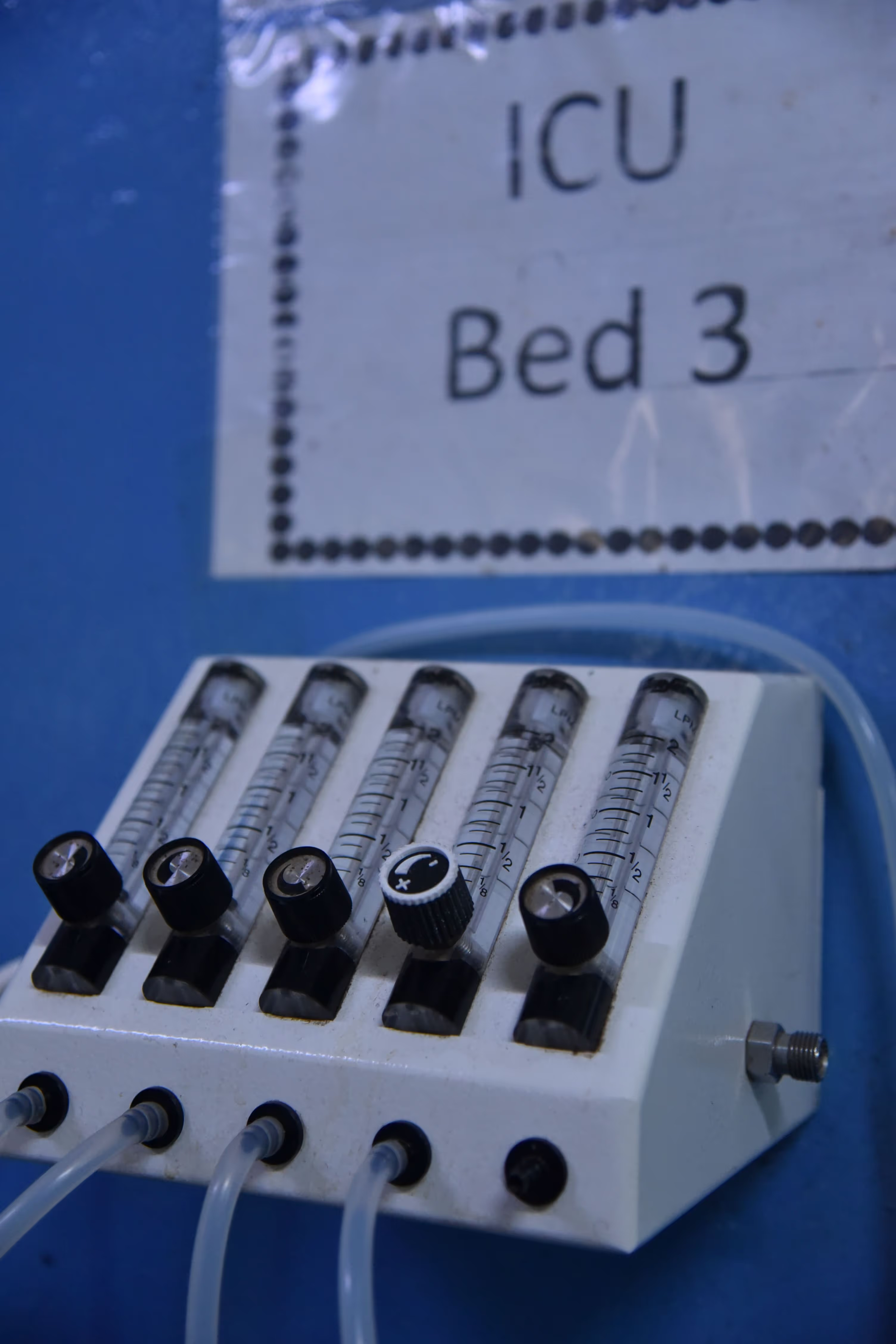

An oxygen concentrator controller in the intensive care unit at Magburaka Government Hospital in the Tonkolili District of Sierra Leone. MSF's 3D printer created a knob that ensures the device's continued functionality. Photo: Daniel Garcia/MSF