Let’s Become Fungal can be read as the culmination of more than a decade of work with the Green Art Lab Alliance (gala), a network of cultural organisations engaging with ecological questions, which Yasmine founded in 2012. It is perhaps no coincidence that we first meet at Quinta das Relvas, a sanctuary for arts and permaculture nestled in the slopes of central Portugal, and itself part of the Alliance. What begins as a conversation about her perspective on the recent surge of interest in fungi soon unfolds into a wider exchange on relationships, reciprocity, and the necessity of collaboration over competition, one of the modes of being at which fungi, unsurprisingly, seem to excel.

Can you tell us about the beginnings of the Green Art Lab Alliance?

It originally began as a EU-funded project focused on reducing the cultural sector’s carbon footprint. We worked with 22 organisations at the time, the intention being to ensure that the knowledge gathered moved in multiple directions rather than flowing in a single line.

When that project ended, everyone was very keen to continue. What quickly became clear to me, though, was that even while we spoke about balancing opportunities and knowledge within Europe, the whole framework remained profoundly eurocentric, almost inevitably so. Over the years, the network grew slowly, almost organically. We are now around 80 organisations spanning Asia, Latin America, Europe, the United States, Canada, and the Caribbean.

Even though in 2012 I probably didn't yet know what mycelium was, the structure already felt very mycelium-like. There was never a central authority. It focused on the exchange of knowledge, nutrients, solidarity, support, information, all moving in an organic, decentralised way.

It has also been about remaining somewhat underground, because the aim of the network was never maximum visibility. Operating below the surface can offer a form of protection, especially in contexts and countries facing censorship or authoritarian regimes, or where environmental activists risk getting murdered for doing their work.

There were so many parallels between the approach we had been cultivating for years and the functioning of fungal ecosystems. Realising that another living system operated in almost the same way, and that it, too, was not about competition but about building relationships across borders, species, and disciplines, opened up an entirely new layer of understanding. The metaphor came later, but the practice was already there.

When did mycology enter your work? Was there a particular turning point?

It felt more like a sequence of things that gradually aligned. Reading Anna Tsing was certainly influential. Around early 2017, I had also started working at the Jan van Eyck Academie as Head of the Nature Research Department, a title that came without a brief nor budget, so I had to invent what it might mean. One of the first things that interested me was mushroom cultivation. I thought it could become part of shaping this new department: building relationships with local growers, visiting their farms, learning from them.

Many people see the Future Materials Bank as a reference point shaped, to a great extent, by your vision. What do materials represent for you?

In my role at the Van Eyck, I was doing many studio visits with artists, listening to them talk about their practice. I could see how much interest there was in engaging with ecology in the widest sense of the word. There was a lot of curiosity, but also a lack of transparency about where materials came from or what their environmental implications actually were. It became difficult for people to make informed decisions about their materials. Even when they genuinely wanted to work in a more ecological way, the path wasn’t obvious.

Future Materials Bank also emerged, in parallel, as a response to seeing so many companies patenting their processes – especially around mycelium. It felt deeply ironic, because the whole organism is about exchange and sharing, yet suddenly the knowledge was being closed off. These two things were happening at the same time: the rise of patents and the general lack of transparency around certain materials.

That became the logic behind the platform: creating a crowdsourced knowledge bank on sustainable materials so people could make more informed decisions and learn from each other’s experiments. You don’t have to reinvent everything yourself; you can build on what already exists. And that felt important, because it serves as a reminder that we’re all ultimately working toward the same goal: shaping a more environmentally responsible sector, practice, world.

By bringing all of that together, you can also show that this is about what can be more exciting. That’s why it was important to me that the platform looked really slick. We can’t keep associating sustainability with something drab or prohibitively high-tech. It needs to feel accessible, inclusive and visually compelling at the same time.

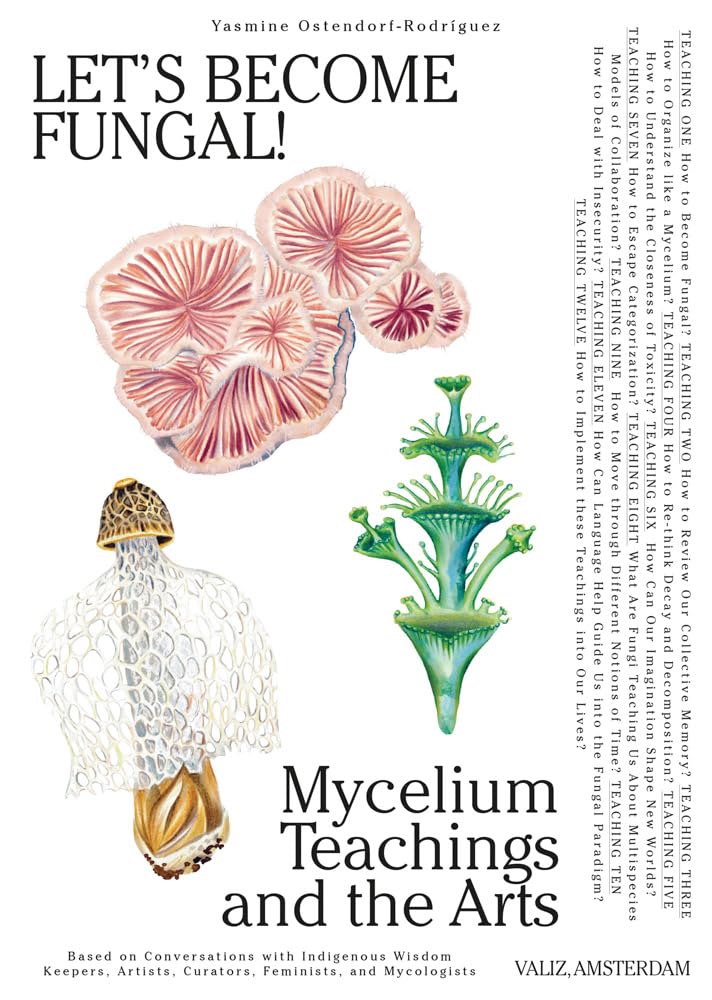

The same applied to the book. It needed to be easy to use, but it also had to be beautiful. You should want to pick it up, to be drawn to it visually.

When I first opened the book, I expected a work on fungi. What I found instead was a book with fungi, one that attends to their relations and entanglements while weaving in detailed insight into the mostly women-led, contemporary workings of the arts and design ecosystem peppered with fascinating stories of your personal journey. What did the process teach you in particular?

It was really important to me that the book would be interesting for people from very different walks of life. That also meant it had to be both deep and bite-sized at the same time. An artist should be able to read it and still feel engaged by the artistic aspects, because they need that to be relevant. But a farmer who knows nothing about the arts should also be able to understand what it’s saying.

Once I started writing, I simply went back to personal experiences, and then linking them to the books I read, the people I admire, and the creatures I admire. So it was partly intentional, but also very organic. And that naturally shaped the emphasis on women creators and knowledge holders across the region.

And then you get the practical question of where it sits on a shelf in a bookshop. Is it an art book? A science book? A book about women? About mushrooms? I honestly feel lucky it was published at all, because it’s a very hard book to market in that sense. I think the beautiful illustrations and the design played a crucial role. They allowed the book to move beyond those categories. That was, of course, very much part of the whole thinking of the book. How can we defy categorization when actually you still need to sit on a shelf somewhere? By making things that don't fit into boxes, you're doing just that.

How did you ensure that contributors were genuinely acknowledged? Did you build any structures of care or reciprocity into the process?

Well, it goes back to relationships of trust. I could not have written the book without ten years of the alliance, which is why it felt important to begin with the alliance itself. When you have relationships that have been nurtured for a long time, reciprocity doesn’t need to be direct or immediately visible, because there is already a shared understanding that things will come back in one way or another.

But it’s a big topic, especially here in Mexico. I see so many researchers who all want to go to Xochimilco, to study the chinampas, or work with Indigenous communities. There is a constant stream of people arriving in the same places, expecting to interview the same communities. And as you know, interviewing someone means asking for their time.

Often the unspoken assumption from the researcher’s side is that what the community “gets back” is visibility. But that is a very limited form of reciprocity, and it doesn’t necessarily address what people actually need or want.

Visibility isn’t always desirable. It’s not automatically positive. Yet we’re so used to thinking in marketing terms, or in the logic of fame – this idea that once people recognise you, your work gains value. And then reciprocity gets reduced to a strange equation: one person gives their time, and the other offers visibility. That’s not a match. It doesn’t align with what reciprocity actually means.

The simplest way is to ask people what they need. It means understanding reciprocity in non-monetary terms as well. We often default to thinking that paying solves everything, as if that automatically balances the exchange. But it doesn’t always speak to what people actually need in a meaningful way.

How do you think we can establish a better relationship also to the underground, mycelial realm?

I write about this idea of understanding the forest as a collaborator, or understanding other beings as collaborators. It requires a completely different way of listening and tuning in, because it asks you to make different decisions about what will benefit them as well as us. It means you have to give something back, whether that’s in terms of biodiversity, conservation, or whatever form of care is needed. I find that a really interesting way of working, not just a thought experiment.

Of course we can never know what it’s like to be a mushroom, or anything else for that matter. But there is a lot of space to think with that, speculate, to imagine it. And simply by observing an ecosystem or a particular creature or entity, you can see when it’s thriving, or when it’s struggling, when it’s growing or shrinking. There is a lot of knowledge held in those shifts. But it usually requires spending time and engaging senses beyond the purely analytical.

Mushrooms are some of the most visible “success stories” in efforts to harness other forms of life within our still very narrow, human-centred frameworks. This success, however, comes with the pressure to fit into contemporary sustainability metrics, taxonomies, ESG logics, and other evaluative systems that we know are constructed from very specific positions of power, by someone sitting...

…sitting still very comfortably in capitalism. Whether it’s mycelium as a material or medicinal mushrooms or anything else, we keep repeating the same extractive mindset: What can it do for me? How can it make me healthier, richer, fix my cancer, clean my house, eat plastic, deal with cigarette butts? It becomes this catalogue of problems we created, and then we look to fungi to solve them so we can continue business as usual. We frame them as tools to repair the damage rather than questioning why the damage keeps happening.

So we reproduce the same pattern of extraction. We don’t use these organisms to critique the system we’re in, or even to consider stepping away from a capitalist structure that keeps producing the crisis. It’s similar in sustainable fashion: “Buy this and you don’t have to feel guilty.” But the logic is still about buying as much as possible, just feeling slightly less awful about it. It doesn’t touch the root of the problem.

What I wanted to do with the book was shift that question entirely: instead of asking what they can solve for us, why not ask what they can teach us?

And no, it’s not a book about “the future is fungi,” and it’s not a book about how delicious they are. Of course there’s a bit of that, but that’s not the point. It’s really about what they are saying to us. What they tell us about all these systems we’re part of. What we can learn from how they organise themselves. There are, I think, important ideas there about how we might restructure society, even financial systems, and how we relate to one another while recognising all these entanglements at once.

So yes, I’m excited that there’s such a growing interest. Not the explosive hype itself, but the curiosity behind it. And I hope it can create some continuity so it doesn’t become a one-off trend before everyone moves on to capybaras. Or whatever comes after capybaras. I’d like the continuity to be in this shift toward learning from them, rather than asking what they can fix for us.

You’ve been touring and staying incredibly active with this book. What has it taught you? And is there something else already taking shape?

Because I love to read, I assumed other people loved to read as well. I learned not everyone has that privilege, time or interest. And I completely respect that. That’s why I developed the Let´s Become Fungal! Oracle Cards: a set of 45 cards with questions, teachings, exercises, meditations, and fungal fun facts. They can be used alone, more in an oracle style, or within a group, a community, an organisation.

Leading workshops has been genuinely fun and incredibly generative. It creates a sense of continuity: the book may be static, but the practice keeps evolving. I’m continuing to do these workshops in different places, and now other people are running them as well. People who simply joined a workshop and then said, “I’d like to do this with my family.” And I’m like, fantastic, here are the tools.

I received a lot of responses to the book. Many of them were amazing, but they also revealed certain gaps or confusions that made me realise there was more to explore. There were also people who were mostly interested in the psychedelic part of the book, which is actually a very small section. And that sits within a much wider discourse about wellness, which in turn sits within a wider discourse on tourism, cultural appropriation, and, again, exploitation. I´m interested in understanding what it means to engage in forms of well-being or wellness that are not culturally or ancestrally theirs.

I find this fascinating because I'm often drawn to practices that are not part of my own culture or ancestry myself, but I’m also aware that this could be potentially problematic depending on how I do that – me as a Dutch woman roaming around the world. There is an issue there, and I’m trying to research the ethics of it. I’m looking at how to navigate wellness practices that are not yours culturally or ancestrally, especially when you’re interested in medicinal mushrooms, plants, and rituals.

So the question becomes: how do you move through that in a way that feels right? Without slipping into the idea that we should all stay in our own cultures and countries or leaning into nationalism, suggesting that we can’t be interested in plants that aren’t “ours,” or drifting into xenophobic logic. That's one of the things I want to write about, because that kind of judgment isn’t helpful. We are attacking one another even though we’re on the same side. It's not helping the bigger struggle in any way if we waste our energy on that.

The interview was conducted in collaboration with the Free Radicals initiative.

%20Josefina%20Astorga%20_%20web-GalaFest-521.jpeg)

%20Josefina%20Astorga%20_%20web-GalaFest-534%20(1).jpg)

%20Josefina%20Astorga%20_%20web-GalaFest-555.jpg)

%20Josefina%20Astorga%20_%20.jpg)

%20Josefina%20Astorga%20_%20%20web-GalaFest-190.jpg)

%20Josefina%20Astorga%20_%20web-GalaFest-255.jpg)