What’s your story, and how did you get started with this project?

I hold a BA diploma in visual communication from the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana, which I completed in 2008 – right at the start of the economic crisis. At the time, it was extremely difficult to find work in the cultural sector.

After graduation, my generation faced a lack of job opportunities, so we had to self-organize and invent our own professional paths. Many collectives emerged, including groups experimenting with social entrepreneurship involving food-related projects and re-use, DIY practices. In a way, the crisis gave me the opportunity to transform my design practice – from contributing to a consumer-driven society to embracing a more ethical and responsible approach – one that has the capacity to question the given, not only serve. Later, a Master’s in Design Futures at Goldsmiths offered me courage, theoretical frameworks, and writing skills to support this direction.

Feral plants caught my attention in 2015 at a fieldwalk we facilitated with the forager Dario Cortese to learn about urban edible flora in the Fužine neighbourhood. This is where the design biennial and its institution, the Museum of Architecture and Design were located.

How did Trajna and Krater come to be connected?

Trajna, the cultural organisation founded by my colleague Andrej Koruza and me, initiated Krater as a production space in a rewilded construction pit. The initial idea wasn’t just to extract biomass of invasive species from the site, but to begin its broader process of regeneration—to create a space for both ecological restoration and material production.

Krater emerged as a collaboration between Trajna, the Permaculture Association of Slovenia, and the Urban design studio Prostorož. These three organisations formed the initial core that launched the project.

The space was set up in 2020, during the early months of the pandemic. With indoor gatherings restricted, it provided an exciting outdoor space for people to come together. In a time of skyrocketing property values, increased loneliness, and the disappearance of autonomous zones in the city, it quickly emerged as a potent site for community building.

Over time, more people joined – artists, architects, photographers, ecologists, volunteers, students, curious citizens – and the project organically grew beyond its founding members. That’s when we began referring to everyone involved as the Krater Collective.

Our group is continuously under construction. People come and go depending on their life circumstances, work, or studies. It includes organizations, individuals, design interns, skaters… What makes it vibrant and resilient is this constant exchange of knowledge, care, and creative resistance to the kind of work offered to us as professionals.

What preceded Krater?

I began working with invasive plants as a topic of design inquiry in 2015. To finance the practice, my organisation at the time started collaborating with the City of Ljubljana on a small-scale grant project. Every year the city invited local NGOs to remove invasive plants from environmentally protected urban areas such as landscape parks or sites of Natura 2000. We drew interest by removing the plants and exploring their material potential – turning biomass into dyes, paper, biomaterials, food, and fertiliser with biologists, soil scientists, mycologists, carpenters, designers and the local residents.

These early endeavours laid the foundation for a three-year project funded by Urban Innovative Actions, a European Union initiative, in which the municipality scaled up our creative approaches into a city-wide circular economy and zero-waste model. We set up disposal units, hosted public workshops, created a collection of DIY wood and paper products, and launched educational activities for schools and the wider community.

The project offered Trajna a unique opportunity to critically reflect on the circular economy approach – particularly in how it reinforces the dominant narrative about invasive species while failing to effectively support actual ecosystem repair. While repurposing invasive plants is better than incinerating them, it doesn’t heal ecosystems – removal often just makes space for new invasive species to grow. We asked: How can we create a regenerative relationship with these sites instead of simply extracting from them?

That question led to Krater. To make a new step in Trajna’s design practice, we decided to inhabit an 18,000 m² rewilded construction site and engage directly with its feral ecology full of invasive plants. We have set up small-scale production spaces – a wood workshop, a paper lab, and a biomaterials studio – which we used not only as functional sites of making products, but as spaces of inquiry where we could explore circular economies as messy, open-ended processes of ecological stewardship.

Entering the site raised key questions: How do you build and produce without interrupting other life-forms on the site? How do you regenerate a space when your presence is only temporary?

The project emerged from a desire to shift the focus from extraction to care, aiming to reframe invasive plants from ecological threats to companion species of the Anthropocene. In an era where globalisation, trade, and industrial production accelerate the movement of species and terraform habitats, these plants are not anomalies but direct outcomes of human-driven ecological processes.

Yet their presence is not solely negative – in disturbed sites like Krater, invasive plants help create fertile conditions for other life forms. We built on their efforts by adding multispecies infrastructures – bird nesting boxes, fruit tree nursery, seedling greenhouse, sanctuary for abandoned potted plants, a pond for feral goldfish, compost toilet, seed banks, while engaging in care work to support the site’s regeneration.

Is Krater mobile or fixed?

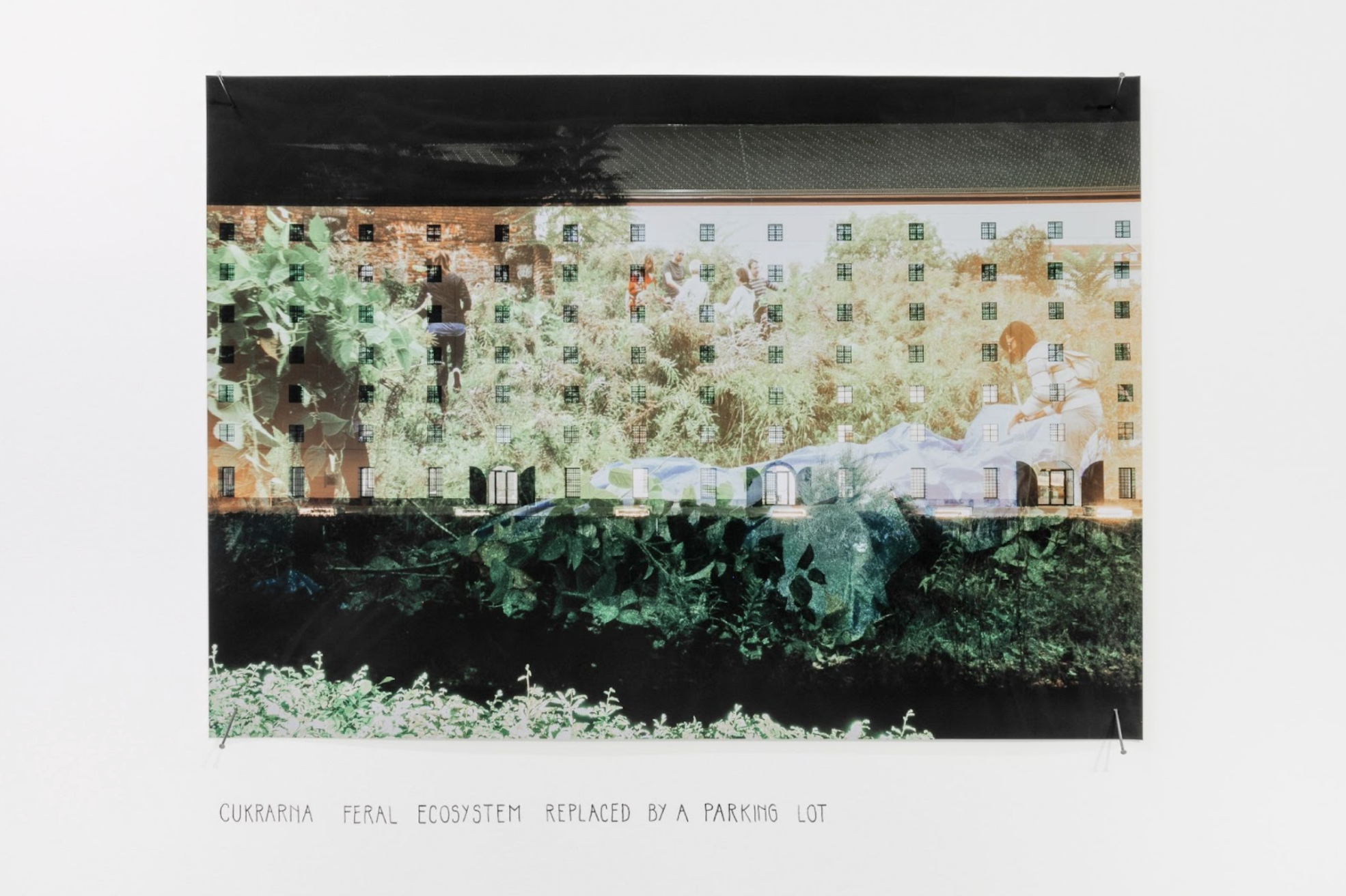

Originally, we envisioned Krater as a mobile, nomadic project. But once we settled on a degraded state-owned site in Ljubljana – we realized the constraints of nomadism packed in the contractual agreement of temporary use. Although the land is earmarked for future development, we’ve repeatedly managed to extend our contract and, together with architect Danica Sretenović, developed a line of advocacy work (such as Feral Palace urgent pedagogies) that gradually repositioned the site’s public image. Through our work, we promote Krater as an urban biodiversity hub and a model of 21st-century urbanism, making it more and more difficult to view the parcel as a site of disgrace or neglect that calls for urban regeneration.

Despite the fact that we had set up “mobile” workshops in shipping containers with the intention of eventually relocating, a deeper relationship with the site began to take root. As we observed seasonal changes, identified local species, and witnessed the ecosystem respond to our care, it became increasingly clear: regeneration takes time.

You can’t build a meadow or restore soil during the course of a one year project. Regeneration requires continuous long-term engagement. While Krater started with a nomadic idea, it evolved into something rooted – because staying became essential to the work of repair.

What ecological role do invasive plants play on the site?

When we arrived at Krater, our perspective on invasive plants began to shift. They weren’t just causing a problem—but taking an active role in ecological regeneration of the site.

On disturbed grounds, invasive plants act as pioneering species that produce large amounts of biomass gradually decomposing into soil; their flowers attract pollinators such as bees and butterflies; and their seeds draw birds to the site. They can change a construction site into a thriving pioneering ecosystem—and contribute to the early stage of ecological succession.

The Krater site had been fenced off since around 1994, after the demolition of Austro-Hungarian artillery barracks. Over time, mosses arrived, birds and winds brought in seeds, and invasive plants likely spread through construction machinery, extracting high-quality gravel from the site. These species were one of the first to take hold – and in doing so, they began restoring life to the site.

Now, over the course of thirty years, a unique pioneering ecosystem has emerged. It’s become one of Ljubljana’s unexpected biodiversity hubs – not just for invasive species, but also for a diverse mix of local and even some rare and protected species.

Research shows that managed city parks and forests can be biodiverse—but these kinds of ecosystems, which arise spontaneously from disturbance and minimal human intervention, are far richer*. Yet they’re unprotected and incredibly rare in urban environments, as most urban greenspace is carefully controlled, regulated and maintained.

*Jogan, N. et al., 2022. Urban structure and environment impact plant species richness and floristic composition in a Central European city. Urban Ecosyst 25, 149–163 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-021-01140-4

What does it mean feral plant?

The terms invasive, exotic, weedy, and non-native are deeply biased. Rooted in colonial notions of pristine nature and nation-state borders, they render these beings as dangerous, harmful, and in need of eradication or displacement. This perspective limits our ability to engage with them in more generative ways.

To help shift practice, we propose a change in language: we call them feral plants. Feral refers to something once cultivated that has gone wild. The term aligns our insurgent design practice with their untamed resilience and invites us to see them as collaborators in a post-anthropocentric world-making project – active participants shaping urban ecologies, where their vital roles are often overlooked.

Is the Notweed paper made at Krater?

No, Krater functions as an experimental and demonstration site only. Notweed paper is produced in a local factory, the harvesting takes place in a feralised garden – abandoned after the passing of the older generation of a family. Japanese knotweed, the feral plant we produce paper from, has since taken over the area after the site became a convenient dumping ground for construction waste during the expansion of a nearby road.

Next to the plot is a beekeeper, a relative of the family, who supports our harvesting efforts. We clear the site in early spring, allowing the knotweed to regrow and provide abundant late-summer forage for his bees. In his opinion, the presence of knotweed also helps prevent urban development in the area.

We harvest in April, when the stems are dry from the previous season, at the same time when the edible shoots start to emerge. We usually come with a tractor with shredding equipment to chop the stems into 2–3 cm pieces and serve knotweed burek pastry to the group of volunteers.

The shredded material is taken to a local factory for pulp production using delignification – a process that removes lignin and leaves cellulose fibers for paper making. The final paper contains about 50% Japanese knotweed fibers and 50% virgin wood cellulose, which is the technical maximum we can achieve.

Compared to other alternative cellulose papers that use only 5–10% non-wood fibers, this is significant. There’s great potential since Ljubljana alone has about 35 hectares of knotweed ‘fields’, and similar sites exist all across Europe.

At Krater, we use our paper mill for pedagogical activities with local school children and makers.

What about other ideas for future applications?

So far, we’ve mostly used the paper for prints: graphics, labels, posters, publications. That’s partly because I come from a graphic design background, so it felt natural to use the material in that way at first. Also, we choose the paper for our eco-social projects, which helps promote our work and show others how the material can be applied.

Do you use dyes?

No, we keep the natural color, but the final appearance can vary depending on the delignification process.

Sometimes the paper comes out paler, sometimes it has a warmer, yellowish tone.

It also depends on whether we include bleached wood cellulose – which we do if the client prefers lighter paper.

If we use unbleached cellulose, the paper is naturally darker. But when legibility is important – like for printed text – bleached paper creates a better contrast between letters and background.

What’s the scale of your paper production, and who purchases it?

We produce around 150 kilograms of paper per harvest, primarily in B2 sheets with 130 and 250 gsm weights. Our main clients at the moment are project partners. For example, we've collaborated with the International Centre of Graphic Arts and the Museum of Architecture and Design in Ljubljana, and more recently with the 42nd Split Salon, for whom we also produced commissioned artworks, workshops, and exhibitions.

Would you say your clients mostly come from the cultural sector?

Yes – we are mostly working with cultural organizations and individual artists.They’re often interested in using the paper for prints, graphic works, or promotional materials. Collaborations usually involve a high level of engagement with our customers. Notweed paper is not a conventional white paper – it has a distinct texture, tone, and material presence that disturbs the logic of standardisation. It asks us to be curious and take time to fully explore its possibilities.

Our dream scenario would be to have a few long-term partnerships – whether with institutions or companies – that commit to using Notweed Paper to replace their unsustainable sources of paper. Having that kind of consistent, longer-term collaboration would create a stable income and allow us to support our work on Krater.

How does Notweed’s economic model challenge traditional approaches?

Notweed Paper challenges mainstream narratives about invasive plants. It serves as a medium for framing an alternative discourse and a practice, not just a product for the market. The paper offers new perspectives on how invasive plants can support disturbed, urban ecosystems and empower communities.

For instance, a zoom call with one of our first customers, an artist Alyssa Dennis, sparked an idea to organise a seminar Invasive Species Creative Proposals Series, bringing together designers, herbalists, permaculturists – people from around the world – who are thinking beyond the war-like approaches to invasive plants. So, what began as a potential sale turned into a much richer collaborative project – showing that successful encounters extend far beyond monetary transactions.

How does Notweed foster connections among people?

We always see our work – especially the Notweed project – as a medium to connect with practitioners and exchange our world-views. That’s something really beautiful and empowering. We collaborate mostly internationally. Our practice is quite niche, and although there are people working on similar topics here in Slovenia, we’ve found more resonance beyond national borders. In May, for instance, Trajna participated in The Spring Symposium on Habitats Through The Perspectives of Art and Science in Brno that had an entire panel dedicated to artists working with invasive plants. It was amazing to see so many presenters challenging dominant narratives and developing more sensible approaches. I think it’s crucial to collectivize our efforts and make them visible – to build a broader community, because there really are quite a few of us. And if we connect, our impact can be much stronger.

Do you also host international visitors?

Creative work at Krater expands the topic of invasive species. It includes biomaterial production, ecological stewardship, and both pedagogical and conceptual work. To sustain ongoing efforts on site in light of its precarity, we advocate for a multispecies right to the city and invent new forms of collectivity that support production of cultural workspaces. Krater’s practice catches the interest of many researchers, PhD and master’s students, curators, performers and active citizens from all around the world who are curious to learn or wish to collaborate.

Last year, for example, Croatian multimedia artist Ivana Papić reached out because of her interest in our work with invasive plants. Together, we explored the material potential of Ailanthus altissima, also known as the Tree of heaven. It’s a feral species native to China and common in urban areas, especially throughout southern Europe. In Croatia, it’s widespread on many islands. The Tree of heaven is often considered a nuisance, but few people are aware of its rich and fascinating ethnobotanical history, including its role in wild silk production. During the residency, we investigated the potential of incorporating this plant into a local silk-making practice. A species of silkworm from China feeds on Ailanthus altissima, and we’re curious about how to craft silk yarns using this relationship.

So is it plant-based silk?

Not exactly. Silk always comes from silkworms, but the interesting part is that these worms feed on different host plants, not just mulberry. In this case, the Tree of heaven. We are interested in crafting "peace silk" or "Eri silk," where silk cocoons are harvested without killing the silkworms.

Is creating a regular residency program part of your future plans?

We already host design student internships every year through Erasmus+. In the future, we aim to welcome more creative practitioners and have recently submitted a project proposal with a residency component. If funded, it will allow us to host a residency program during the course of the project. But our vision of residencies is a bit different. We insist on co-production – embedding visiting artist’s work with the collective’s ongoing efforts with the site. There's always a lot to manage – plant care, site visits, infrastructure maintenance, event facilitation, grant writing, administration – and we're a small team. Instead of risking overexhaustion, the collaborative experience becomes mutually enriching – we benefit from fresh perspectives and extra hands on site, and the artists become part of a living process. It’s more meaningful for everyone involved.