„For me, it is very important how people experience things around them“, says the exceptionally friendly designer and co-owner of a shop which carries everything one may need for enjoyable dining. From September 25 to November 22, the Prague´s Kuzebauch Gallery exhibits, on a nicely set table, her glass bowls which strive to engage our perception of spatial arrangement.

What made you go to Japan right after the high school?

I had a roommate who spoke a lot about Japan. I got very inspired by her stories and decided to go there right away – an idea which I was stubborn enough to make true.

How did you get there?

I took a train and then a ship. I had just two months there. It was really an adventure because I did not know anybody there. In Japan, you have to get introduced to get to virtually any place, so I ended up getting almost nowhere.

What happened next?

At the end, I met a landscape architect who wanted to help me. He had studied and lived in Denmark for many years and he helped me return to Japan. He arranged for me to study and work at a ceramic workshop. The workshop was the first place where I worked and studied before I would continue at a college or a university. I actually learned a lot about art and crafts there.

Were you studying traditional ceramic techniques? What was the studio like?

It was a very open minded space and at that time – the name of the town was Tokoname – people came in from several places in Japan to work there. They busied themselves with different things, but their original product was something called uekibachi. They made plant pots and tableware as well as some big public contracts. I was there doing virtually everything. In a way, I was a labourer there – in the morning they would tell me what to do on that very day - help glazing, fill the kiln, or anything else.

Do you remember any special tasks?

Soon after I joined them, they asked me to decorate some of their tableware. They just told me to do whatever I liked and I had to invent something. It was really challenging.

Were there more young people like you?

At that time, they had maybe three or four young people there and we had our own little space where we could work in the evenings.

What did you do in the evenings?

I started to learn how to work with some traditional things such as rokuro. It’s a potter´s wheel – which is actually the opposite way as in Denmark. Everything in Japan is the other way.

How did your day look like there?

After one year I was doing a lot of packing. Actually, after one year I said - I’m a bit tired now. For months, I kept doing this really boring work. And they said fine, that’s ok, you can stop doing this and we´d give you space to work on your own stuff all the time. So I worked on my own projects there and one of the employers became like a mentor to me. He showed me so much… He even taught me how to build a Japanese kiln and we built this kiln together. Then I was firing this kiln and doing a lot of work. At the end, I produced a lot of stuff and at their regular annual market I managed to sell it all, enough to pay for my trip home.

It sounds like a fairy-tale…

And then I went through China, I was travelling alone for six weeks and that was just an amazing adventure because China had just opened for individual travellers. To get home, I took a train from Beijing to Berlin.

It seems you learned a lot in Japan. But when you came back to Europe, you decided that you needed more education. Why was that?

I needed a place where I could work. So I applied for a Ceramics Course at the Danish Design School. Actually, it was not called the Danish Design School at that time, it was the School of Applied Arts. I attended the course and it was also fantastic. I was making ceramics for two years and then I had an opportunity to apply for glass, too. I said to myself – will you ever get a chance to try glass somewhere else? And the answer was - Ok, let´s try glass.

And glass won you over?

Yes. And then I studied glass for three years.

Can you describe the difference between your Japanese experience and the European schools?

It has to do a lot with people I was with. My mentor Norio inspired me quite a lot. Norio was the guy in the factory who had a big say in how they produced things and he was very hard working. I learned a certain approach to work from him and adopted his way of problem solving. When I got back, I started the course. I really wanted to go to the workshops and work but there was a kind of laid back atmosphere there among the schoolmates– if you compare it to my experience from Japan.

Did Japanese culture get under your skin?

There are so many beautiful things in Japan but I never wanted to adopt their culture. It is interesting to see all this beauty but I want to do it my own way.

My mentor Norio and my friend Ibata were very free thinkers. Their Japanese cultural background is very strong, but the same is true for their personalities. They have a very interesting combination of the two in them – stick to the roots but have your own personality. When you go to Japan, you meet a lot of foreigners who overdo it – they adopt the Japanese way of making ceramics so deep that it ends up looking more Japanese than the Japanese stuff itself.

Is it because it’s easier for them? Or easier to sell?

I don’t know, but in a way it is just the outer shell, this work doesn’t come from them, it’s more like a wrapping.

What was the approach promoted by the school?

At that time, the Danish school taught you quality crafts. We were making functional things such as tea pots. It was rather old fashioned, but I learned a lot anyway. When I studied at the glass department, there was not much teaching there other than instruction of the techniques – I learned to blow and to work with other techniques – but it was not about projects where you have to solve things. So I had to think to develop everything there by myself.

Was it worth the effort?

For me it was very important to learn something about the materials and to play with it. But my experience in Japan was absolutely the most important thing for me.

What is the main difference for you in working with these two materials – glass and ceramics?

The ceramics is directly accessible and you can mould it directly with your hands which is something I actually miss with glass. With glass I learned basic techniques – I know how to blow glass but I can’t do it myself so I have to work with craftspeople who do it for me. So I’m always kind of distant to the material. It’s a big difference and therefore the conversation between me and the people who do the work becomes very important.

Do you find it difficult to find people to work with? Good people to transform your ideas in the material?

It’s difficult to find people. But now I’m lucky. I started working in Novy Bor, the Czech Republic, about fifteen years ago. Now I work with a group of people there and they are very precious for me to work with. Sometimes I wish to find other people for some other projects and it’s difficult indeed.

Because of the level of their craftsmanship? Or because of communication problems?

It’s difficult because of the language barrier – I know I should be looking here in the Czech Republic because there are specialists here in a lot of glass related aspects, but it’s difficult not only given the language barrier but also quality wise - sometimes it´s hard to find people capable of delivering the quality that I would like.

How did you first come to the Czech Republic to work with Czech craftsmen and factories?

I wanted to start my own production of glass. I kept asking around and my Swedish colleague who had worked with Petr Novotný told me to try and contact Petr. I did that he said I should come over, so I went to the Czech Republic to meet him. Then I worked with the same group in Ajeto for a long time. This relationship has become better and better and it means a lot to me, that we can develop things together.

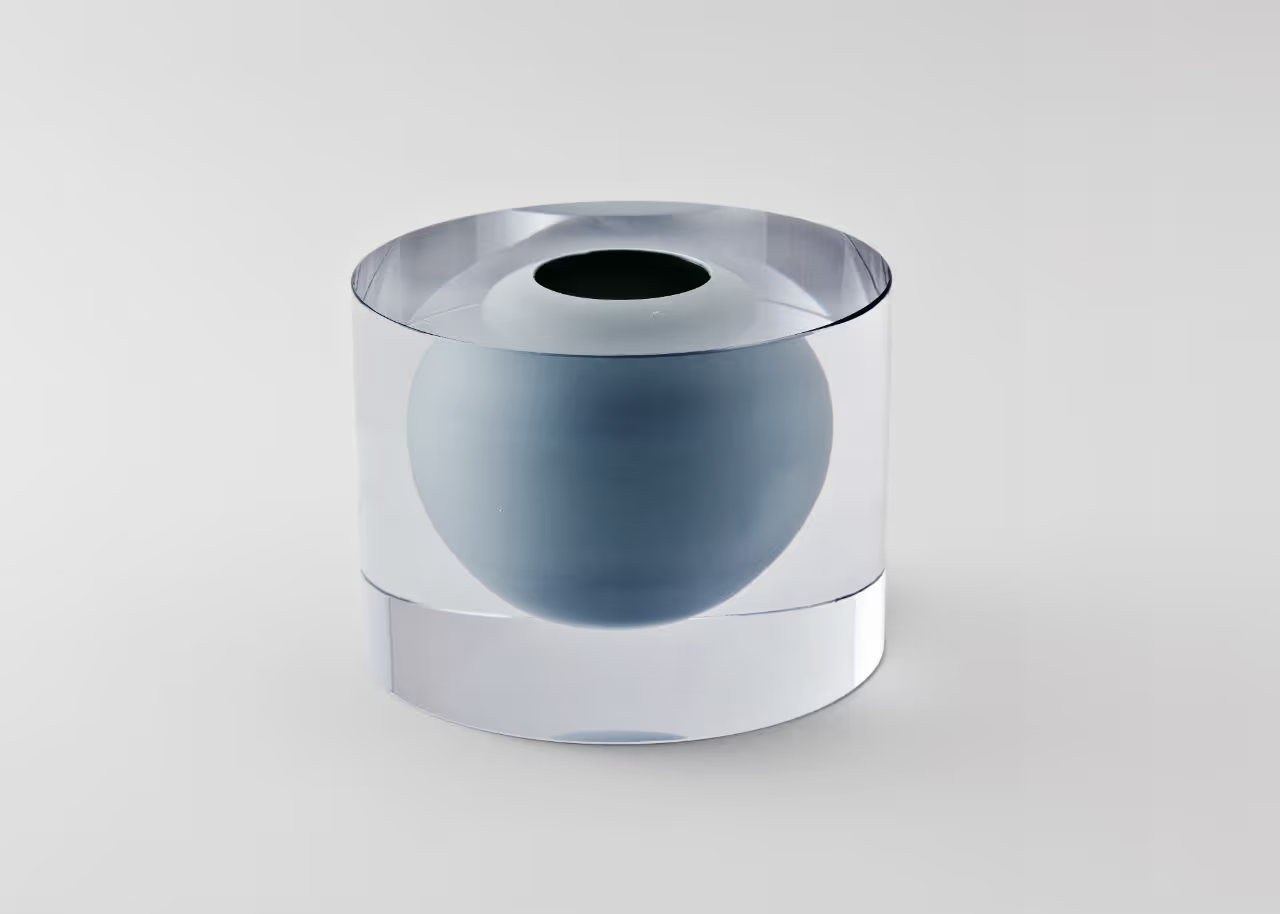

This double wall bowl – was it your first glass project?

Yes. It was my first glass project in the Czech Republic but, of course, I had done a lot of other glasswork before coming here.

Are you still developing things around the same idea?

Maybe this also relates back to my Japanese experience. I find it very interesting to create this kind of frame where you really can go on exploring something – go into the depth - and it becomes more and more interesting in a way.

In subtle details?

You know, some people are going to ask me – why don’t you make something new? But for me it’s new all the time, I explore something with the colours and the tones of colours – you can do so many things – thickness of colours, thickness of glass. That’s what I find really fascinating.

Is it minimalism? You don’t call it minimalism, do you?

I don’t know, I don’t call it minimalism. But I am interested in the small variations - how much little change can do.

Why did you first make a bowl? Was it about the border between the applied and the high art?

I’m very interested in the border and in the crossover, too. The same is true for the functional work. For me, it is very important to observe how people experience things. Like the connection with an object and a person. For example the object that you can take in your hand. But also how you perceive the object visually.

What do the bowls mean to you?

The double wall bowls were originally an idea about the bowl but definitely thinking about the visual idea. And then the visual idea somehow took over. But it’s very important to still keep the bowl because it’s like an archetype shape that everybody knows and it’s a very strong image. Everyone can relate to it. If it was just like a box or something very abstract, it would not have the same effect.

Ondřej Strnadel who exhibited in the Kuzebauch Gallery last year and whose big theme are the blown bowls told me, that what he finds interesting about this bowl thing is the inside/ outside tension – is it also interesting for you?

Absolutely. It was a starting point in a way. You are thinking about how to make the wall – how can you look at the wall of the bowl and express the inside and outside and what is in between. What’s in between the inner and the outer walls?

What does the designing process mean to you?

I look at my work a lot asking myself – is this exciting? Or what about this colour, maybe I should try this and make notes and then I make a plan for ok, now, I’m going to try this and see what will happen.

And this something happens in the glass factory or later during the cutting process?

Both. It’s also about a mix of decisions you take. It can be about proportions, the outside surface or many other things. It’s both nerve wrecking and exciting.

Do you have pieces that you thought were going to look great and when you finished them you realized you´d never exhibit them?

Absolutely, I have my studio in Denmark full of pieces, that I don’t know what to do with. Things can go wrong in the glass making process. I make a big body of work and then I choose the best pieces.

What do you do with the rest?

Some of the rest I use like reference. Sometimes I can see - this is a beautiful colour I will try this again and then improve the shape or something. So nothing is lost, it’s just a bit painful to have to store all these things.

What are you searching for?

In a way I’m always searching for the same thing – it’s just expressed in different ways.

And what is that?

It’s something I can see in the material that could be visually strong. I keep asking – how can I use the nature of the glass – the material and its colour?

Both in a controlled way but also letting things happen in the process and make use of that.

Have you ever thought about making glass bowls in series?

I have made some series of glass bowls when I collaborated with Fritz Hansen, a Danish furniture company which sold some of my work. And of course the functional pieces I make in small series. But items like those on display in this exhibition I do not wish to produce in series.

Why?

It’s a very complex process to make these pieces. Some of these pieces cannot be replicated. They look simple but it’s not so simple to make them (Some pieces can be replicated as to their idea or colour, I can make a maximum of five pieces there, if customers would like to buy exactly this. But they never look the same anyway.). It is also much more interesting for me to try some new variations.

Do you care about bowls, plates and glasses in you daily life?

I do. I like things where somebody had thought about how the food would look like in it and how would you eat or drink from it.

As we were sitting in the Cafe 8 – have you looked at the glasses, the plates?

Yes, I looked at them. It’s important as it becomes a part of our daily life. And these things we hold in our hands everyday and we use them, we depend on them but they can be so badly neglected… I think that young craftsmen should think more about that.

Maybe there are just a few people who would care about such things as table culture, don’t you think?

There’s a lot of cheap stuff that people just buy to have some glasses and then you throw it out and get some new. And then there are things that are very status minded and that you see in some interior magazines and you think – Ok, I should also have this ... and then of course there are people who take interest in such things and can see their beauty.

Maybe we can speak here about the value of the stuff?

Yes the value, but look at the crafts. I don’t know how it is in the Czech Republic – but where I come from making functional ware doesn´t have the same status. And choosing to work with drinking glasses or bowls for eating- it doesn’t have the same value as making art objects. But for me, it has absolutely the same value and I enjoy doing all my work equally.

Why is that?

It’s a matter of putting your energy into that. And I think functional ware is of great importance, too. But it doesn’t have the same status. In a way, it’s more complex to make a functional piece, because you have to think how it should be used.

What is characteristic of an object which fails in it´s execution?

I don’t like when things are pretentious. I don’t like trying to make art. So therefore I also prefer not to call my work art. For me this word has been very much abused. Anyway, it’s a long discussion about art and craft. A lot of craft people want to be artists and it can become a disaster.

But for you it’s more convenient not to use the word art.

In a way, it gives more freedom.

Maybe the word craftsmanship will loose this meaning as well. The word can sell, so it´s maybe loosing it´s meaning as well.

Yes, it’s true. It’s abused as a marketing tool. It’s like thinning the meaning.

Do some of your colleagues ask you to comment their work?

Yes sometimes. But I don’t have so many discussions with people. I miss talking about things. It´s nice to have a dialogue.

You have a shop/gallery in Copenhagen that you co-own with friends. You exhibit and sell functional tableware in limited series there. Actually there is an exhibition of the beverage sets and bowls from Rostislav Materka by now. What is the point of this business?

We’re seven people and we can share our ideas. And it’s not about glass, it’s more about crafts and design and its place under the sun. Even though there’s a lot of work in our pieces and lots of thoughts, our prices are not very high, as it is functional ware. In fact, we cannot make our living just from this shop. We just have it because we think it’s important.

Are your colleagues there from the same background?

It´s five ceramists, one textile designer and me. Our idea is to elevate the functional ware – to make it precious. It’s nice to have beautiful things, it matters. And we also like to present other people´s work that we find interesting. So it also functions as a kind of gallery.

Do you actually believe that when you use beautiful things it can elevate our mind? That one would become a better person?

Yes..... But I don’t know if it can have such a big influence.

Maybe it can elevate our sensitivity?

Yes, absolutely.

You are a very sensitive person. Have you ever wished to change that? Perhaps because it‘s hard this way?

Of course it can be difficult to be sensitive, but you have to deal with it somehow.

And I think that’s why I’m doing what I’m doing , that I’m sensitive. Because it’s like sensing things you know. I wouldn’t call myself an artist but I am in a way sensing things and then expressing them.

That’s a good definition of art.